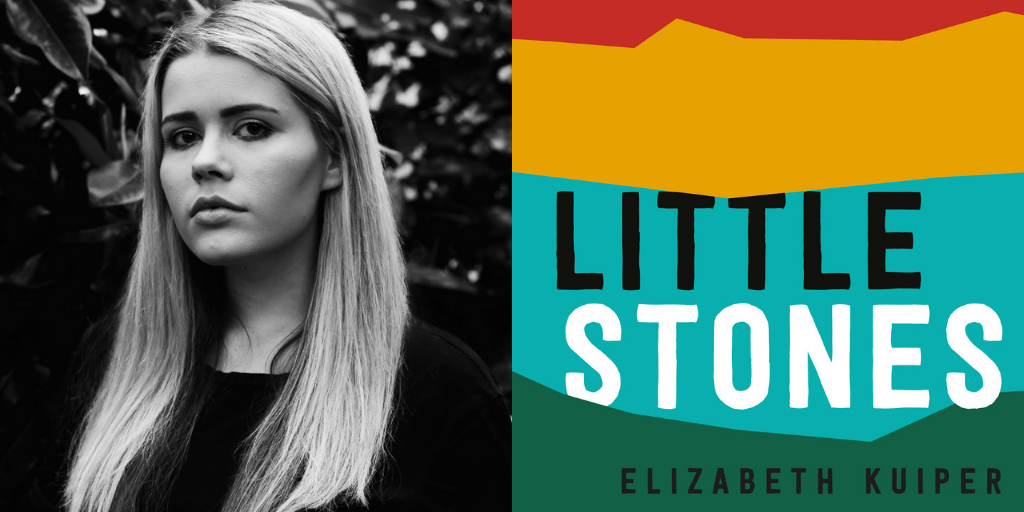

Earlier this month saw the publication of Elizabeth Kuiper’s debut novel Little Stones. The novel, which draws upon Kuiper’s own childhood experiences, follows the story of Hannah, a young white Zimbabwean as she navigates everyday life in a country under the control of Robert Mugabe.

Following the novel’s release we sat down with Elizabeth to chat about the novel, its creative journey and what she hopes readers might take away from the novel.

Your character, Hannah, grows up white in Zimbabwe during the time that Robert Mugabe was in power. How similar is her experience to your own?

Hannah and I have a lot in common. We both grew up in Mugabe-era Zimbabwe. We were both part of the white minority and consequently held positions of privilege. We were also both raised by single working mums. I definitely drew on these experiences and interrogated my own history in order to bring Hannah to life.

I think there are, perhaps, a lot of ‘big-picture’ similarities, but Hannah remains a fictional character with her own unique way of looking at and interacting with the world. There are also a multitude of lived, day-to-day experiences that Hannah and I share but aren’t particularly unique. Regular power-cuts and water-cuts, paying with billion-dollar notes, swerving to avoid potholes in the road, was just the way life was for almost everyone. When my mum and I lived in Zimbabwe, we experienced multiple home invasions which, while frightening and traumatic, were not atypical.

Hannah’s point of view in the novel allows the reader to see the political situation in Zimbabwe through the eyes of a young girl, just reaching her adolescence, and we begin to make sense of things (or struggle to) as she does. It’s a fantastic way to introduce the landscape of the time without having to overexplain. Was it difficult to achieve Hannah’s voice and point of view?

Sometimes it was tricky because I would feel a desire to insert myself and my opinions into the story. Part of this came from a fear that the reader may take Hannah’s uncritical worldview at face value. I had to remind myself that Hannah is eleven and not yet capable of having a sophisticated and nuanced view of race or gender politics. As tempting as it was to overexplain, or have Hannah indulge in some heavy-handed moral retrospection, I think I knew I should be giving the reader more credit. We also see Hannah slowly beginning to unpack her privilege and explore some of these ideas as the narrative progresses, but in a way that stays true to her age.

Hannah and her parents are white, but she has a number of strong relationships with people of Shona heritage such as her housekeeper Gogo and her best friend Diana. With race such a volatile issue, and representation always being scrutinised, was it difficult to strike the right balance in the portrayal of your different characters’ backgrounds and circumstances?

I’ve frequently been privy to discussions in which non-African people advance an idea of Africa as a homogeneous continent and espouse a bizarre dichotomy in which its people are either impoverished and living in remote communities, or wealthy, corrupt politicians in gilded mansions.

It was important for me, firstly, to delineate Zimbabwe as a country with its own unique history and people. It was also important for me to show black Zimbabweans as precocious school kids, the working mothers of those school kids, as bank-tellers, as gay theatre-aficionados, as psychologists and teachers, as well as farm workers and housekeepers. Not just because representation is important (it is), but because that’s the reality. It wouldn’t be true to the country or my experiences of it to write otherwise.

When writing Little Stones, I really tried to focus on creating well-rounded characters. Having fully formed characters, with their own backgrounds and personalities, enabled me to explore not only issues of race, but the economic divide in the country as well. Diana Chigumba is Hannah’s best friend who also attends Bishopslea, the private girls’ school. Diana and Hannah both live in big houses in the suburbs, they share the same interests and hobbies, they’re both intelligent and mature for their age. They’re ostensibly one and the same, which allows for their close bond. Their similarities are also a great way to unpack the ways that they are not – while both girls are middle-class and privileged in that regard, throughout the novel we see that Diana is subject to the racism of white Zimbabweans, sometimes in ways so insidious that Hannah may not even realise.

You’ve been quoted as saying ‘Writing Little Stones helped me reclaim this part of my identity and to make sense of my memories.’ How, specifically, did writing help you do this? What was the process of writing the novel like?

When I first arrived in Australia, I struggled a bit to fit in and definitely felt a disconnect between myself and my peers. But I was still quite young, and I think kids are generally pretty malleable. The longer I spent in Australia, the more I felt I belonged, which was undoubtedly a good thing. The tough part was feeling as though I had lost a little part of myself. My accent became warped, I started calling swimming cozzies ‘bathers’ and flip-flops ‘thongs’, I picked up on all the pop-culture references. I even started very half-heartedly barracking for a football team (Go Freo!) But there was something missing and there was stuff from my past I couldn’t talk about with my peers because they either didn’t care or didn’t understand. I think writing about my childhood was really incredibly cathartic and it was through that process I felt I was able to reconnect with my past.

When did you first decide that you were going to be a writer?

I’ve always loved to write. I can’t pinpoint any moment in my life where I ‘decided’ to become a writer. When I was in Grade 4, a short story I wrote about the adventures of a talking bicycle won the prize for my year group at the Zimbabwe institute of Allied Arts. The other day I was going through some old things and reminiscing, when I came across the story and the judge’s handwritten comments, who wrote that he thought I would grow up to become an author, or something to that effect. So, I think someone knew about my path before I did. And perhaps I’ll hone in on this talking bicycle idea for the next book?

Little Stones has just been published by University of Queensland Press, a small publisher with a big reputation for publishing exciting voices in Australian fiction. How did you come to have your book published by them, and what was it like working with the UQP team?

Little Stones began as a 3000-word short story for a creative writing unit I took in my undergrad. It was published in Voiceworks in 2014 and off the back of that I was asked to read an excerpt at the Wheeler Centre’s ‘The Next Big Thing’. My current publisher, Aviva Tuffield, sent me an email the following morning to express her interest in my writing and asked me to keep her in mind should I produce anything in the future. Several years later when I had a rough MS draft of Little Stones, she was the first person I reached out to and the rest is history.

The UQP team, including Aviva, have been incredibly lovely and supportive. It’s evident that they are a group of people with a genuine passion for great storytelling. Jean Smith, the UQP publicity and events coordinator, has also been a really encouraging and positive influence, often fielding all my anxious-debut-author questions (of which there have been plenty).

You’ve lived in Zimbabwe, then in Perth, and now in Melbourne? Are any of these places more ‘home’ to you?

Am I allowed to be cheesy? If so – I feel like home is where the heart is. Along with the big country and city moves, I’ve also moved houses maybe eleven times in my life, so I’ve never really developed a deep attachment to physical places. The only real constant in my life has been my mum – so whenever I’m close to her, I feel like I’m home.

A version of Little Stones was longlisted for the Richell Prize and you received the Express Media prize for the best work of fiction—what impact did receiving these accolades have on your work?

It definitely gave me the confidence boost I needed to keep writing, knowing that my voice was one that people were interested in and that I had created something special with this story.

What do you hope that readers will take away from reading your novel?

I think there’s so many things, that if readers took away just one, I’d be happy. If readers learn about Zimbabwe and its rich, unique history, then go on to read books by other Zimbabwean authors – that would be brilliant.

If they appreciated the representation of Jane as a single working mum, and the way the book explored the acrimonious divorce between Hannah’s parents – that’s also good.

If the only thing a reader took out of the book was learning some Shona words or the names of a few Zimbabwean cities, I still think it’s pretty cool that I was able to pass on that knowledge.

Are you working on anything new at the moment?

As tragic as it sounds, my main goal for this month getting through law exams and post-publication madness. After that winds down, I reckon I’ll be able to embark on a new project.

![]()

Elizabeth Kuiper’s Little Stones is available now through University of Queensland Press (UQP). You can find our review of the novel HERE.